Source: Open letter to Dan Tehan

Source: Open letter to Dan Tehan

Reducing student fees in so-called ‘priority fields’ – namely STEM, health and teaching – is a key plank of the proposed higher education funding reform package. Whilst the Government has signaled to students, and to all Australians, that it takes investment in priority fields very seriously, severe funding cuts to higher education providers delivering these courses tells a very different story. One in which the Government is seeking to make budget savings by reducing teaching and scholarship capacity opportunistically across a number of key disciplines.

Teaching and learning funding explained

Funding for domestic undergraduate places in Australia comprises two components. The first is the student fee contribution and the second, the government grant component. Traditionally the Government grant was intended to cover the part of the cost not met by the student.

Figure 1 Components of course funding on a per student basis

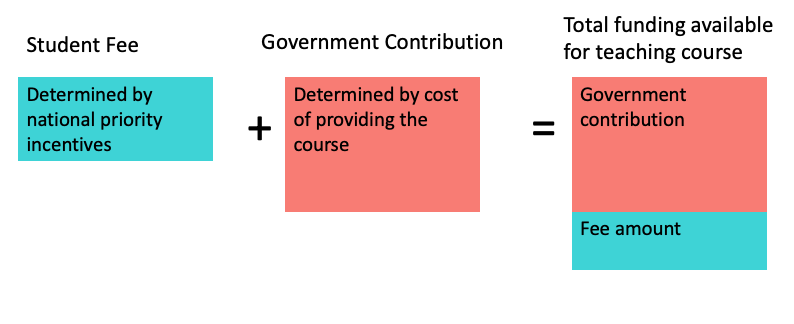

It can be seen in Table 1 below1 that the net effect of the funding reforms will be to reduce funding for ten of the fifteen priority fields, with Science and Engineering losing thousands of dollars per student. By far the biggest hit is to Environmental Studies courses, which are set to lose close to ten thousand dollars per student.

The few areas that do gain, such as Architecture and IT, will generally see only small increases of around five-hundred dollars. English and Literature seems to be the only real winner from this reform package, with a funding bump that is both curious and nonsensical given the relatively low overheads.

Table 1 Total change in funding per student for all disciplines

New funding levels based on questionable data

The Government has claimed that its proposed reductions are “in line with contemporary evidence on the cost of delivering university education,” and that many courses are ‘over-funded.’ They have come armed with figures to support this claim.

Those figures, however, are highly questionable. A few years ago, the Government embarked on a project to determine the cost of higher education teaching and learning across different areas. Deloitte Access Economics were enlisted, collecting information from Universities regarding the actual cost of teaching. This project has culminated in the 2019 Transparency in Higher Education Expenditure Report, from which the Government derived the ‘average teaching cost’ of twenty-two individual subject areas. These numbers underpin the new funding levels.

This is problematic, as the process of gathering reliable data on the cost of teaching is still very much a work in progress. Many Universities lack sufficiently sophisticated cost estimation processes to provide reliable figures. The Deloitte Report indicates that, of the Universities that participated, around 40% do not have the capacity to estimate the costs of course delivery at subject level. Presumably, they are relying on top down ‘guesstimates’ inferred from Department, or Faculty level data. Only 32 of 37 Universities were included - top ranking institutions such as The University of New South Wales, University of Technology Sydney and La Trobe University have yet to participate.2.

In addition, there are some strange anomalies in Deloitte’s methodology. Of note, the reporting has aggregated ‘Allied Health’ (ie practical component courses such as Paramedic Studies and Radiology) with ‘Other Health’ (ie theory-based health courses such as Public Health and Rehabilitation Studies). Traditionally, the two have been treated separately and belonged to different funding clusters, owing to the capital heavy nature of ‘Allied Health’. The Report provides a single average for all Health courses, thereby providing an appropriate estimate for neither. ‘Allied Health’ and ‘Other Health’ are now to be funded at the same level for the first time since the funding cluster system was conceived in 1989.

Slim operating margins will devastate capital intensive courses

The impact of COVID-19 is reverberating across the University sector - the loss of international student fee revenue has cut deeply and will continue to hurt in the short and medium term. Modelling by the Centre for the Study of Higher Education shows the sector is set to lose A$19 billion by 2024.

At the same time, the Tehan reforms will radically reduce operating margins. The reduction in margins is illustrated in Figure 2, which shows the funding levels against average teaching costs in 2018, and the proposed funding levels against average teaching costs in 2021 (applying a 6% cost increase over three years).3

Under the proposed reforms, the operating buffer for courses is negligible. Many Agriculture and Environment courses will fail to break even, and Health courses will be operating on a knife-edge.

Figure 2 Total funding against average cost of teaching by Discipline (2018 and Proposed)

The importance of the present funding buffer cannot be overstated, and not only because Universities with a large share of international students have found themselves in financial straits.

There is significant variation in teaching costs in priority fields between Universities, for good reason. Courses that include a high practical component face significant non-recurring capital costs, in the form of updating facilities and equipment every few years. The proposed reforms do not allow for slack in the system to make these critical one-off expenditures necessary to maintain the relevance of labs, test equipment and field work gear that is used by students.

For example, Figure 3 shows the estimated costs facing individual Universities delivering Engineering and Health courses in 2021. These figures were obtained from the Department of Education, Skills and Employment. Once again, a cost increase of 6% was applied.

Under the new funding arrangements, more than a third of Health courses and more than half of Engineering courses will no longer break even.

Figure 3 Course costs across 32 Universities - priority fields

In terms of more general strategies for cost cutting, Deloitte’s 2016 Cost of Higher Education Report sheds some light on the features of higher education that can be leveraged to reduce the bottom line. In that report, the key identified drivers of cost variation were:

Staff-student ratios;

Workforce casualisation; and

Research intensity (for high cost fields of education)

In short, the changes we can expect to see within the higher education sector, as Universities grapple with fee revenue loss and funding cuts, are larger class sizes, increased teaching by junior staff on insecure contracts, and fewer opportunities for students to undertake research.

Reducing students’ exposure to research will significantly limit the possibility for vital knowledge transfer between senior staff and students. The logical outcome of the reforms, namely lower quality graduates, is completely at odds with the Government’s stated aim of “increasing the supply of highly skilled and knowledgeable workers able to drive innovation within business, develop and adapt to new technologies, and undertake basic and applied research.”

The proposed higher education reforms will constrain the ability of Universities to provide places for graduates in areas of demand, as well as undermining Australia’s skills base for future innovation. They are insupportable even within the limits of the Government’s own rhetoric. Imposing these cuts in 2021 in the current financial climate will have devastating results. Institutional cuts, once made, cannot be easily unmade. The reforms are not based on sound data, not fit for purpose, and wilfully blind to the reality of the recession. Higher education reforms must align spending with institutional capacity to deliver high quality graduates, in critical areas. At the very least, the Government must commit to getting the numbers right.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

The data in the table was obtained directly from the Federal Government discussion paper Job Ready Graduates: Higher Reform Package 2020, pp 17-18↩︎

Also not included in the sample: Macquarie University and Western Sydney University↩︎

Costs for 2021 were derived by applying an annual cost increase of 1.95% to the 2018 estimates over a three year period (6% over three years). The underpinning reasoning is discussed in Professor Andrew Norton’s article,Can a Block grant work on lower per student funding rates↩︎